Fugitive Voice

by Martha Feldman

Read free of charge for a limited time

In this essay Martha Feldman proposes that current-day notions of fugitivity, understood in the terms Fred Moten delineates as a category of the irregular that escapes easy representations and predications, can undiscipline music histories in productive ways. Among these: it can inflect musicological thinking through attention to sonic remainders of haunted pasts; it can decenter understandings of the aesthetic; and it can lead to more nuanced thinking about the imbrication of music in an “undercommons” of life that refuses ever to fully sound in harmony, residing instead in a disordered space of restless, noisy sound. Feldman asks, finally, how such thinking, developed by Moten, Nathaniel Mackey, and Daphne Brooks, among others, can remake aspects of musicological thinking about voice.

In this essay Martha Feldman proposes that current-day notions of fugitivity, understood in the terms Fred Moten delineates as a category of the irregular that escapes easy representations and predications, can undiscipline music histories in productive ways. Among these: it can inflect musicological thinking through attention to sonic remainders of haunted pasts; it can decenter understandings of the aesthetic; and it can lead to more nuanced thinking about the imbrication of music in an “undercommons” of life that refuses ever to fully sound in harmony, residing instead in a disordered space of restless, noisy sound. Feldman asks, finally, how such thinking, developed by Moten, Nathaniel Mackey, and Daphne Brooks, among others, can remake aspects of musicological thinking about voice.

The essay begins:

A vibrant strain of avant-garde writing is nowadays centering music as the medium of a luminously varied Black radical aesthetic without much of musicology yet noticing. Such work might bring to mind sonic points along a dolorous history, from “the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs” of slaves traveling to receive their monthly food allowance that Frederick Douglass heard on the plantation—what W. E. B. Du Bois called “sorrow songs,” “through which the slave spoke to the world”—to the stirring blues laments of Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, and Nina Simone brought to light by modern-day Black feminists. Today’s Back avant-garde stretches out from such moments, addressing long histories of racial subjugation and violence intimately bound up with modern histories of capitalism, but it’s up to something different. It understands its aesthetic objects through a nexus of politics, philosophy, and metaphysics that often goes by the name of fugitivity, a concept that encompasses those earlier soundings while resituating them. Not restricted to literal flight from slavery, fugitivity belongs to what philosopher and poet Fred Moten—thus far its most expansive and challenging theorist—describes as a capacious category of the irregular in which freedom and unfreedom perpetually coexist in persons who refuse to be objectified or reduced. Only when a Black being recognizes their oppression, victimization, or commodification by speaking, talking back, or refusing to be named and delimited does fugitivity become a lived reality. Only then does it move in its characteristic temporal arc, bending toward the future even while haunted by a past that is never past. Moten conveys this existential condition in a disarming passage about the resonance between the slave narrative passed down to posterity by Harriet Jacobs (1861) and a nude photograph of an anonymous prepubescent Black girl captured in 1882 in the studio of Philadelphia artist Thomas Eakins:

The moment in which you enter into the knowledge of slavery, of yourself as a slave, is the moment you begin to think about freedom, the moment in which you know or begin to know or to produce knowledge of freedom, the moment at which you become a fugitive, the moment at which you begin to escape in ways that trouble the structures of subjection that—as Hartman shows with such severe clarity—overdetermine freedom. This is the musical moment of the photograph.

Provocatively, fugitivity here, regardless of its expressive medium, has a consistency that is decidedly musical.

I want to pause at this juncture—obscure at its surface, for how can a photograph without an iota of literal sound have a “musical moment”?—because the notion is pivotal, turning on what Moten elsewhere calls “visible sound.” Avid readers of Moten will recall another photograph that clamors at various points in his prose, that of the desecrated body of young Emmett Till, whose mother insisted he be displayed in all the horror of his savage murder. The image contains what Moten calls an “extensional cry and sound,” one whose power to overtake the viewer’s senses ignites the memory with a disturbance that transduces other senses, other embodied memories.

An image from which one turns is immediately caught in the production of its memorialized, re-membered reproduction. You lean into it but you can’t; the aesthetic and philosophical arrangements of the photograph . . . anticipate a looking that cannot be sustained as unalloyed looking but must be accompanied by listening and this, even though what is listened to—echo of a whistle or a phrase, moaning, mourning, desperate testimony and flight—is also unbearable. These are the complex musics of the photograph. This is the sound before the photograph.

The music sounds before the camera clicks, before the viewer views, and sounds again once the viewer looks. Music both precedes and expresses Black life. It triggers memories that turn into griefs and horrors, more images, and (as we learn elsewhere) bundles of sensory events beyond the strictly auditory or visual. Not just unidirectional, however, medial/sensory transformations and intermediations also go the other way. Hence Jacobs, at a devastating moment in her account, hears “a band of serenaders . . . under the window, playing ‘Home Sweet Home,’” which soon turns into the sounding image of moaning children.

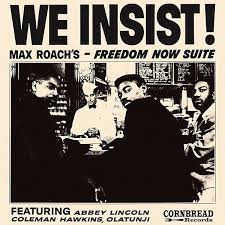

Music here is no more resident solely in physical sound than in sounding music. Wherever found, Black music registers fugitive escape via the phonic eruption, which equates to Black experience and is prefigured by the scream or cry whose originary American instance (to which Moten turns twice, following Saidiya Hartman) are the screams of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester being viciously beaten by her owner. Contained “in the break” (the main title of Moten’s first book), the cry disrupts conventional grammars, strictures, and forms, indexing a breakdown or breakage, but also, relatedly, a breakthrough—a Black event that moves the subject from bondage, conscription, and silence to flight, marronage, and voice. Such flight takes the form of a literal (and for Moten paradigmatic) scream in Abbey Lincoln’s performance of Max Roach and Oscar Brown Jr.’s Freedom Now Suite (1960), a piece that is otherwise “musical” in the ordinary sense. But fugitive flight also takes other sonic forms: a plangent, wailing jazz solo; the explosive shouts in James Brown’s “Cold Sweat”; the lyrical, dancing rhythms of Rakim’s hip-hop, for example—all instances of Moten’s philosophies repeatedly articulating the Black radical aesthetic that Michael Gallope describes “as folds, blurs, oscillations, and rewinds; as displacement and dispossession; as the entanglement of lyricism, performativity, improvisation, and virtuosity.” Continue reading …

Music here is no more resident solely in physical sound than in sounding music. Wherever found, Black music registers fugitive escape via the phonic eruption, which equates to Black experience and is prefigured by the scream or cry whose originary American instance (to which Moten turns twice, following Saidiya Hartman) are the screams of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester being viciously beaten by her owner. Contained “in the break” (the main title of Moten’s first book), the cry disrupts conventional grammars, strictures, and forms, indexing a breakdown or breakage, but also, relatedly, a breakthrough—a Black event that moves the subject from bondage, conscription, and silence to flight, marronage, and voice. Such flight takes the form of a literal (and for Moten paradigmatic) scream in Abbey Lincoln’s performance of Max Roach and Oscar Brown Jr.’s Freedom Now Suite (1960), a piece that is otherwise “musical” in the ordinary sense. But fugitive flight also takes other sonic forms: a plangent, wailing jazz solo; the explosive shouts in James Brown’s “Cold Sweat”; the lyrical, dancing rhythms of Rakim’s hip-hop, for example—all instances of Moten’s philosophies repeatedly articulating the Black radical aesthetic that Michael Gallope describes “as folds, blurs, oscillations, and rewinds; as displacement and dispossession; as the entanglement of lyricism, performativity, improvisation, and virtuosity.” Continue reading …

MARTHA FELDMAN is the Edwin A. and Betty L. Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Music at the University of Chicago. Her books include Opera and Sovereignty (Chicago, 2007), The Castrato (Oakland, 2015), and the coedited The Voice as Something More: Essays toward Materiality (Chicago, 2019). She is now working on a book on castrato phantoms in twentieth-century Rome.

MARTHA FELDMAN is the Edwin A. and Betty L. Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Music at the University of Chicago. Her books include Opera and Sovereignty (Chicago, 2007), The Castrato (Oakland, 2015), and the coedited The Voice as Something More: Essays toward Materiality (Chicago, 2019). She is now working on a book on castrato phantoms in twentieth-century Rome.

Representations board member Ian Duncan will give the 2021

Representations board member Ian Duncan will give the 2021

“Lately, across the humanities, historicism in its many guises has been in retreat—a retreat that music studies has in some respects hastened. This collection of essays asks why sound and music appear to induce exhaustion with history and historical method and how a renewed focus on musical practices might motivate fresh histories and novel forms of history writing.” –from the editors’ introduction

“Lately, across the humanities, historicism in its many guises has been in retreat—a retreat that music studies has in some respects hastened. This collection of essays asks why sound and music appear to induce exhaustion with history and historical method and how a renewed focus on musical practices might motivate fresh histories and novel forms of history writing.” –from the editors’ introduction In reading Henry James’s late novel The Wings of the Dove with Honoré de Balzac’s Seraphita, Amy Hollywood argues that James performs through his novel an act of secular devotion, a memorialization of lost others through which he enables himself to continue to live.

In reading Henry James’s late novel The Wings of the Dove with Honoré de Balzac’s Seraphita, Amy Hollywood argues that James performs through his novel an act of secular devotion, a memorialization of lost others through which he enables himself to continue to live.  In the eighth book of Henry James’s late novel The Wings of the Dove, the young orphaned American heiress Milly Theale has a party. She has rented a Venetian palace from which she is too ill to leave. She is even too sick, although she refuses to acknowledge it, to come down for dinner. But she will, her companion Susan Stringham tells Merton Densher, one of the three key figures in this (doubly) failed marriage plot, come down after dinner, to a candlelit frescoed room filled with music. (“He had found Susan Shepherd alone in the great saloon, where even more candles than their friend’s large common allowance—she grew daily more splendid; they were all struck with it and chaffed her about it—lighted up the pervasive mystery of Style.”)

In the eighth book of Henry James’s late novel The Wings of the Dove, the young orphaned American heiress Milly Theale has a party. She has rented a Venetian palace from which she is too ill to leave. She is even too sick, although she refuses to acknowledge it, to come down for dinner. But she will, her companion Susan Stringham tells Merton Densher, one of the three key figures in this (doubly) failed marriage plot, come down after dinner, to a candlelit frescoed room filled with music. (“He had found Susan Shepherd alone in the great saloon, where even more candles than their friend’s large common allowance—she grew daily more splendid; they were all struck with it and chaffed her about it—lighted up the pervasive mystery of Style.”)

GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, founded in 1993, offers an exemplary site for understanding the rise of queer theory, which, from the start, has struggled with the tension between institutionalization and radical resistance. By situating the emergence of this journal and queer theory in general within the AIDS crisis and the literary tradition of the elegy, this essay offers a reading of conventional academic practices as rituals of queer melancholia that comes to challenge the assumption of queer theory’s secularity.

GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, founded in 1993, offers an exemplary site for understanding the rise of queer theory, which, from the start, has struggled with the tension between institutionalization and radical resistance. By situating the emergence of this journal and queer theory in general within the AIDS crisis and the literary tradition of the elegy, this essay offers a reading of conventional academic practices as rituals of queer melancholia that comes to challenge the assumption of queer theory’s secularity. KRIS TRUJILLO

KRIS TRUJILLO

This article offers a reading of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 experimental text DICTEE as performing purposefully ambiguous devotional work. As a meditation on unfinished struggles against colonial and patriarchal violence, DICTEE registers devotion’s role in both oppression and liberation. Cha’s engagements with female martyrs, Korean mudang shamanic practice, and colonial languages demonstrate the inseparability of structures of domination and traditions of resistance. The essay argues that even as DICTEE wrestles with inescapable forms of complicity, its efforts to transform perception denaturalize the violence of racial, gendered, and political divisions.

This article offers a reading of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s 1982 experimental text DICTEE as performing purposefully ambiguous devotional work. As a meditation on unfinished struggles against colonial and patriarchal violence, DICTEE registers devotion’s role in both oppression and liberation. Cha’s engagements with female martyrs, Korean mudang shamanic practice, and colonial languages demonstrate the inseparability of structures of domination and traditions of resistance. The essay argues that even as DICTEE wrestles with inescapable forms of complicity, its efforts to transform perception denaturalize the violence of racial, gendered, and political divisions. ELEANOR CRAIG

ELEANOR CRAIG