Brushes, Burins, and Flesh: The Graphic Art of Karel van Mander’s Haarlem Academy

by Aaron Hyman

The essay begins:

With male bodies of deep brown-reds, and others of an eerie bluish cream, Cornelis van Haarlem’s enormous Fall of Lucifer pulses warm and cool at once, creating an energy more appropriate to a bacchanal than to a scene of damnation. The canvas’s surface is filled with naked men: a bare butt turns out to us in the foreground, knotty flesh is seen through gently parted thighs, scrotums punctuate splayed legs, and penises respond to the forces of gravity. Insects, traditional iconographic elements of northern European depictions of falls from grace, are here used to conceal genitals. Yet, ironically, the insects instead serve to fix our attention on male groins. The man standing at the left side of the canvas renders sexual innuendo explicit, as his outstretched hand leads the viewer’s eye toward two men in an overtly sexual position. Across the canvas, the strange foreshortening creates the illusion that the reclining nude in the foreground stares directly at the anus of the man who straddles his face. A penis and testicles appear to hang just inches from this reclining man’s nose.

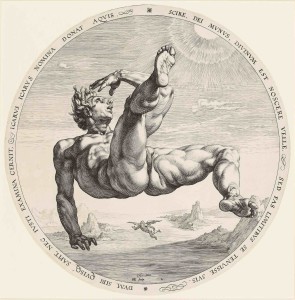

H. Goltziuz, Icarus, 1588. c. Trustees of the British Museum, London. Use by Creative Commons Copyright.

These are the figures of Karel van Mander’s so-called Haarlem Academy, a mysterious and posthumously applied term for an important group of artists who collaborated for a brief, but intense, period at the end of the sixteenth century. The figures in this painting instantiated a web of relationships between the members of this “academy”: the painter Cornelis van Haarlem, the engraver Hendrick Goltzius, the patron Jacob Rauwert, and the art theorist Karel van Mander. These men—a theorist and chronicler of art and his closest colleagues—quite literally defined the northern European canon as it was taking form at the end of the sixteenth century. In the year this painting was begun, 1588, the work and lives of these four men were profoundly interconnected, entwined with the sprawling, muscular, nude men of their art. It was the same year in which Cornelis painted a second, highly disturbing work—Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon (The National Gallery, London)—one that is equally important to exploring the relationships of this group. In Karel van Mander’s renowned artistic treatise, Het Schilder-Boeck, these two canvases are signaled as the high point of Cornelis’s early career; Goltzius made reproductive prints after them; and Rauwert, to whom a print of the Cadmus piece was dedicated, owned both. These works acted as nodes through and around which relationships between these men were formed and conceptualized.

Probing these works and the collaborative working conditions that brought them into being, this essay explores how making art in the early modern period could create a representational space in which relationships could develop and be worked through. With its distinctive treatment of naked male bodies, The Fall of Lucifer points toward a homoerotic dimension of the Haarlem Academy and of this type of collaborative milieu of making in the period more generally. This essay does not pursue a claim—and, indeed, dispenses with the expectation—that the painting evidences (or even could evidence) homoerotic encounters that took place between these men in Haarlem, in the world. Such an interpretive tack has become standard in an early modern art history seeking to give voice to the makers and users of art from within a silenced space of the homoerotic—or homosexual, as is often claimed post hoc for the early modern. Art historians have often proceeded from the belief, explicit or not, that art has the potential to present homosexuality, the desires or sexual practices of makers that become represented in the work of art and that might be confirmed by dint of historical documentation to verify such a reading. The charge made during the social turn out of which much of this now-canonical literature on homoerotism in the early modern period emerged was to give the picture a weight equal to that of the written word in documenting personal (erotic) experience. But if the artwork might offer the art historian initial insight into social dynamics, it is nevertheless inscribed as the historical and methodological endpoint: practices existed, they were documented, and the work of art represents them. The stake in choosing how to treat the work of art is therefore nothing less than the relationship between representation and history. Continue reading …

This essay examines the erotic works produced collaboratively by members of Karel van Mander’s so-called “Haarlem Academy” to suggest that early modern art making created a space in which slippages could occur between homosocial relationships and homoerotic practices. Hierarchical power relations inherent to collaboration, and to early-modern precursors to formalized academies, facilitated these dynamics because they structurally replicated essential conditions of homoerotic relationships. In turn, the piece proposes ways in which formal readings of works coupled with the interrogation of collaborative artistic production can help explore how works of art do more than index homoerotic relationships and, instead, instantiate them.

AARON M. HYMAN is a PhD candidate in the Department of History of Art at the University of California, Berkeley, and currently the Andrew W. Mellon fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts (2015–17) and Mellon fellow in Critical Bibliography at Rare Book School (University of Virginia). His research has also been supported by the Social Science Research Council, the Belgian American Educational Foundation, and the Jacob K. Javits fellowship.

My analysis is premised on a concrete connection between the seemingly disparate fields of modern Japanese literature and Hayekian neoliberalism: In 1957, the most famous novel of modern Japan, Kokoro (1914) by Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), was translated into English by Edwin McClellan (1925–2009), who was at the time one of Hayek’s advisees on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. McClellan was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Scottish father, and he counted both Japanese and English as native languages. The novel he translated while working with Hayek, Kokoro, is a literary masterpiece that centers on the relationship between an alienated university student and an older man, known only as “Sensei” (my teacher), who shares his thoughts on the loneliness of the modern world with the student before committing suicide just after the death of the Meiji Emperor in 1912.

My analysis is premised on a concrete connection between the seemingly disparate fields of modern Japanese literature and Hayekian neoliberalism: In 1957, the most famous novel of modern Japan, Kokoro (1914) by Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916), was translated into English by Edwin McClellan (1925–2009), who was at the time one of Hayek’s advisees on the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago. McClellan was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Scottish father, and he counted both Japanese and English as native languages. The novel he translated while working with Hayek, Kokoro, is a literary masterpiece that centers on the relationship between an alienated university student and an older man, known only as “Sensei” (my teacher), who shares his thoughts on the loneliness of the modern world with the student before committing suicide just after the death of the Meiji Emperor in 1912. If, for Henry David Thoreau, “hospitality is the art of keeping you at the greatest distance,” then no one was more hospitable than Thomas Carlyle; after all, Carlyle’s ability to keep his friends at a distance was no less than his ability to keep them. Nothing Americans might think, after the publication of his Latter-Day Pamphlets in 1850, could heal over the wound they felt straightaway that Carlyle “mocked the admiration” he lived to gain and that, for all the gratitude he had toward us, he also, says Henry James Sr., “hated us.” There may have been “an inexplicable rapport,” writes Walt Whitman, between himself and Carlyle, but, judging by Carlyle’s anti-egalitarianism, bigotry, and scorn of democracy, Whitman was “certainly at a loss to account for it.” Who could excuse, and in any case who could deny, the harmful effect of Carlyle’s contempt for abolitionism, suffrage, and social reform? He “stands for slavery,” Ralph Waldo Emerson writes; he “goes for murder, money, capital punishment” and is as “dangerous as a madman. Nobody knows what he will say next or whom he will strike.” Apparently, vegetarianism bothered him. If you praised republics, he liked Russian czars. If you urged free trade, he remembered he was a monopolist. “Cease to brag to me,” says Carlyle, “of America and its model of institutions and constitutions…. They have begotten, with a rapidity beyond recorded example, Eighteen Millions of the greatest bores.” The press describes his work “On Heroes”—his attempt to substitute a new “hero-archy” for lost hierarchies in society and government—as a recipe for “unadulterated despotism” and “more especially how to catch masses of people and indoctrinate them with the feeling of obedience.” When we read his essay “Dr. Francia,” an apology for the supreme dictator of Paraguay, it is not hard to see why, by the 1930s, Carlyle’s theory of the hero seemed compatible with German fascism or that essays from that time, including “Carlyle Rules the Reich,” suggest that Hitler’s own belief in his “fulfillment of duty” to the majorities could “be expressed in familiar old phrases from Carlyle.” In 1945, when Joseph Goebbels tried to dispel Hitler’s sense of defeat, he read to him from Carlyle’s book on Frederick the Great–Hitler’s favorite book.

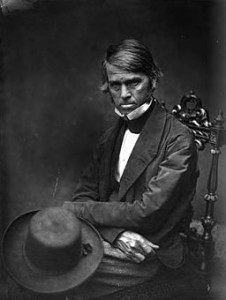

If, for Henry David Thoreau, “hospitality is the art of keeping you at the greatest distance,” then no one was more hospitable than Thomas Carlyle; after all, Carlyle’s ability to keep his friends at a distance was no less than his ability to keep them. Nothing Americans might think, after the publication of his Latter-Day Pamphlets in 1850, could heal over the wound they felt straightaway that Carlyle “mocked the admiration” he lived to gain and that, for all the gratitude he had toward us, he also, says Henry James Sr., “hated us.” There may have been “an inexplicable rapport,” writes Walt Whitman, between himself and Carlyle, but, judging by Carlyle’s anti-egalitarianism, bigotry, and scorn of democracy, Whitman was “certainly at a loss to account for it.” Who could excuse, and in any case who could deny, the harmful effect of Carlyle’s contempt for abolitionism, suffrage, and social reform? He “stands for slavery,” Ralph Waldo Emerson writes; he “goes for murder, money, capital punishment” and is as “dangerous as a madman. Nobody knows what he will say next or whom he will strike.” Apparently, vegetarianism bothered him. If you praised republics, he liked Russian czars. If you urged free trade, he remembered he was a monopolist. “Cease to brag to me,” says Carlyle, “of America and its model of institutions and constitutions…. They have begotten, with a rapidity beyond recorded example, Eighteen Millions of the greatest bores.” The press describes his work “On Heroes”—his attempt to substitute a new “hero-archy” for lost hierarchies in society and government—as a recipe for “unadulterated despotism” and “more especially how to catch masses of people and indoctrinate them with the feeling of obedience.” When we read his essay “Dr. Francia,” an apology for the supreme dictator of Paraguay, it is not hard to see why, by the 1930s, Carlyle’s theory of the hero seemed compatible with German fascism or that essays from that time, including “Carlyle Rules the Reich,” suggest that Hitler’s own belief in his “fulfillment of duty” to the majorities could “be expressed in familiar old phrases from Carlyle.” In 1945, when Joseph Goebbels tried to dispel Hitler’s sense of defeat, he read to him from Carlyle’s book on Frederick the Great–Hitler’s favorite book.