by Ian Duncan

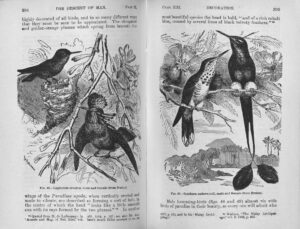

Arguing that aesthetic preference generates the historical forms of human racial and gender difference inThe Descent of Man, Charles Darwin offers an alternative account of aesthetic autonomy to the Kantian or idealist account. Darwin understands the aesthetic sense to be constitutive of scientific knowledge insofar as scientific knowledge entails the natural historian’s fine discrimination of formal differences and their dynamic interrelations within a unified system. Natural selection itself works this way, Darwin argues inThe Origin of Species; in The Descent of Man he makes the case for the natural basis of the aesthetic while relativizing particular aesthetic judgments. Libidinally charged—in Kantian phrase, “interested”—the aesthetic sense nevertheless comes historically adrift from its functional origin in rites of courtship.

Arguing that aesthetic preference generates the historical forms of human racial and gender difference inThe Descent of Man, Charles Darwin offers an alternative account of aesthetic autonomy to the Kantian or idealist account. Darwin understands the aesthetic sense to be constitutive of scientific knowledge insofar as scientific knowledge entails the natural historian’s fine discrimination of formal differences and their dynamic interrelations within a unified system. Natural selection itself works this way, Darwin argues inThe Origin of Species; in The Descent of Man he makes the case for the natural basis of the aesthetic while relativizing particular aesthetic judgments. Libidinally charged—in Kantian phrase, “interested”—the aesthetic sense nevertheless comes historically adrift from its functional origin in rites of courtship.

The essay begins:

In The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871), Charles Darwin sought to write the definitive version of an experimental genre of philosophical anthropology, the “natural history of man,” pioneered—and disputed—in the late Enlightenment by the Comte de Buffon, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, Johann Gottfried Herder, Immanuel Kant, and other major thinkers as the realization of a universal science of man. With the delivery of human species being to secular history and geography, the old question of human exceptionalism had come to bear with a new urgency on the point at which, and means by which, the human emerges from animal life and comes into its own. Friedrich Schiller’s treatise On the Aesthetic Education of Man (Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen, 1795) forged a crucial link between this philosophical anthropology and divergent traditions, scientific and humanist, of nineteenth-century aesthetic inquiry. Where the history of man splintered among competing disciplinary claims on scientific authority, Schiller’s reframing of its main question, human becoming, as a project of individual development—an education—established a program for the modern humanities or liberal arts. The humanist legacy of the Aesthetic Education is well studied. Less so is its anticipation of Darwin’s key idea, that the aesthetic sense is the medium of a specifically human evolution, in The Descent of Man. More is at stake in the comparison between Schiller’s and Darwin’s conjectural histories of human emergence than an accounting of possible influence. Scrutiny of their common concerns and differences illuminates the originality of Darwin’s own contribution—still insufficiently appreciated—to nineteenth-century aesthetic theory.

On the Aesthetic Education of Man posits an instinct or faculty Schiller calls the “play-drive” (Spieltrieb), which affords the full realization of human nature through the aesthetic apprehension of form. The last letters of the Aesthetic Education sketch a conjectural natural history of this coming-into-humanity. The play-drive originates in animal life, in the body, in the “sheer plenitude of vitality, when superabundance of life is its own incentive to action.” Overflowing physiological function, the life force manifests itself as play. In the case of humans, it springs beyond the determinations of biology (need) and anthropology (custom):

Not content with introducing aesthetic superfluity into objects of necessity, the play-drive as it becomes ever freer finally tears itself away from the fetters of utility altogether, and beauty in and for itself alone begins to be an object of his striving. Man adorns himself. Disinterested and undirected pleasure is now numbered among the necessities of existence, and what is in fact unnecessary soon becomes the best part of his delight. (211)

Torn from the fetters of utility, beauty in and for itself alone: Schiller’s conjectural history yields the dominant conception of the aesthetic in nineteenth-century writing—a crux, as we shall see, in recent accounts of sexual selection, the agency Darwin identified as shaping human evolution, by historians and philosophers of science.

Commentary on the Aesthetic Education of Man has downplayed Schiller’s late turn to natural history, in which the aesthetic apprehension of form marks the transition from the animal to the human state. Discussions of the work’s Victorian legacy tend to prioritize one of the terms of Schiller’s title over the other, the aesthetic or education. The aesthetic education provides a disciplinary program for what Herder called a Bildung der Humanität, a “formation of humanity” or evolutionary perfection of human species being, in his most ambitious of late-Enlightenment philosophical anthropologies, Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (Ideas for a philosophy of the history of mankind). Pedagogical projects to foster and direct “the general harmonious expansion of those gifts of thought and feeling which make the peculiar dignity, wealth, and happiness of human nature” in the individual person—constituting “our humanity proper, as distinguished from our animality”—supply the precondition for projects of social and political reform in the best-known Victorian version of the aesthetic education, Matthew Arnold’s. In Culture and Anarchy Arnold pays tribute to Schiller’s legacy in the educational system bequeathed to the Prussian state by Wilhelm von Humboldt. Later Victorian affirmations of the aesthetic reacted against its conscription into didactic programs and regulative systems. Schiller’s Twenty-Second Letter became a “locus classicus for Victorian aesthetes,” according to Angela Leighton, as they sought to repatriate aesthetic experience to individual sensuous life. “In a truly successful work of art, the content should effect nothing, the form everything,” Schiller wrote, defining “the real secret of the master in any art: that he can make his form consume his material” (155–57). The Oxford editors of the Aesthetic Education note that the biological metaphor implicit in Schiller’s word vertilgen, “consume,” that is, digest, metabolize, disappears in Victorian reformulations, which “make it sound as though Schiller wants to empty art of subject-matter if not of content” (267; clxxvi). “To make form obliterate, or annihilate, the matter will be the difficult, sometimes guilty, sometimes provocative, aim of Schiller’s aestheticist followers,” Leighton comments, citing Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde.

The triumph of form over content or material in order to constitute it as the proper object of aesthetic attention points behind Schiller to Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment, which prescribes form’s purification from contingent sensuous interest. More decisively than Schiller, Kant wrested the aesthetic away from its earlier modern meaning of “sensitive cognition” or “sensuous knowledge” (Alexander Baumgarten’s term), by positing sensuous intuition (the imagination) and cognition (the understanding) as distinct faculties, to prescribe the alignment of subjective perception with universal norms of judgment. German idealism broke with a largely British empiricist tradition of scientific aesthetics, developed in eighteenth-century medico-physiological treatises, which grounded aesthetic effects in sensation and the body—in William Hogarth and in Edmund Burke, the sexed and gendered body. The empiricist tradition, with its conception of aesthetic form as “a concordance between the human mind or body and the order of nature,” continued however to flourish in nineteenth-century Britain. Scholarship “has continued to under-estimate the importance of physiological and evolutionary aesthetics in shaping discussions of art and beauty in the 1870s and 1880s,” writes Jonathan Smith, citing John Ruskin’s late work Proserpina. Benjamin Morgan recovers the links between canonical writers on aesthetics, including Ruskin and Pater, and Victorian scientific materialists, whose “aspiration to uncover a formal patterning in nature eventually extended to an interest in a physiological patterning of the body and the nervous system, whose attunement or non-attunement to nature’s forms provided one explanation for the experience of beauty or ugliness.” Continue reading …

IAN DUNCAN is Florence Green Bixby Professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the editorial board of Representations. His books include Modern Romance and Transformations of the Novel (Cambridge, 1992); Scott’s Shadow: The Novel in Romantic Edinburgh (Princeton, 2007); and, most recently, Human Forms: The Novel in the Age of Evolution (Princeton, 2019).

Representations board member Ian Duncan will give the 2021 Wolfgang Iser lecture on June 30, 2021 (9:00am PDT). The talk, entitled “The Fiction-Making Animal: Revisiting Literary Anthropology,” will be streamed over Zoom here.

Representations board member Ian Duncan will give the 2021 Wolfgang Iser lecture on June 30, 2021 (9:00am PDT). The talk, entitled “The Fiction-Making Animal: Revisiting Literary Anthropology,” will be streamed over Zoom here.

Every previous major disaster in human history, from the Black Plague to the Great Depression, has elicited a reimagination of the world, a reinvention of collective life through culture. The COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. The arts and humanities—two areas of inquiry that focus on value and meaning—provide crucial resources for reconceptualizing our lives together during, and after, our current crisis.

Every previous major disaster in human history, from the Black Plague to the Great Depression, has elicited a reimagination of the world, a reinvention of collective life through culture. The COVID-19 pandemic is no exception. The arts and humanities—two areas of inquiry that focus on value and meaning—provide crucial resources for reconceptualizing our lives together during, and after, our current crisis.

Arguing that aesthetic preference generates the historical forms of human racial and gender difference inThe Descent of Man, Charles Darwin offers an alternative account of aesthetic autonomy to the Kantian or idealist account. Darwin understands the aesthetic sense to be constitutive of scientific knowledge insofar as scientific knowledge entails the natural historian’s fine discrimination of formal differences and their dynamic interrelations within a unified system. Natural selection itself works this way, Darwin argues inThe Origin of Species; in The Descent of Man he makes the case for the natural basis of the aesthetic while relativizing particular aesthetic judgments. Libidinally charged—in Kantian phrase, “interested”—the aesthetic sense nevertheless comes historically adrift from its functional origin in rites of courtship.

Arguing that aesthetic preference generates the historical forms of human racial and gender difference inThe Descent of Man, Charles Darwin offers an alternative account of aesthetic autonomy to the Kantian or idealist account. Darwin understands the aesthetic sense to be constitutive of scientific knowledge insofar as scientific knowledge entails the natural historian’s fine discrimination of formal differences and their dynamic interrelations within a unified system. Natural selection itself works this way, Darwin argues inThe Origin of Species; in The Descent of Man he makes the case for the natural basis of the aesthetic while relativizing particular aesthetic judgments. Libidinally charged—in Kantian phrase, “interested”—the aesthetic sense nevertheless comes historically adrift from its functional origin in rites of courtship.

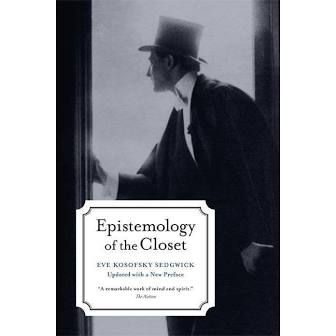

Published in 1990 (with a portion initially written as early as 1983–84), Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet was written in the mid- and late-1980s context of an “open season on gay men” in public discourse (as she put it)—not to speak of gay bashing and an apocalyptic medical crisis. By now there’s an extensive secondary scholarship on Sedgwick’s literary criticism and queer theory. But to my knowledge none of it pursues the thread I’m going to try to draw out here.

Published in 1990 (with a portion initially written as early as 1983–84), Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet was written in the mid- and late-1980s context of an “open season on gay men” in public discourse (as she put it)—not to speak of gay bashing and an apocalyptic medical crisis. By now there’s an extensive secondary scholarship on Sedgwick’s literary criticism and queer theory. But to my knowledge none of it pursues the thread I’m going to try to draw out here. Three distinguished UC Berkeley scholars—

Three distinguished UC Berkeley scholars—