by Alexander Nemerov

The essay begins:

The huge explosions could be heard more than twenty miles away. A Union major named James Connolly lay asleep on the ground, exhausted after the day’s fighting, when he and his men “were aroused by sound of distant explosions away off to the North.” General William Tecumseh Sherman, encamped nearby and leading the Union army, uneasily heard the sound of shells exploding in the direction of Atlanta just after midnight. He and his aides debated what the blasts meant and woke a nearby farmer, who said that the battles around Atlanta sounded like that. Still, no one was sure. The sounds died down but then renewed at 4:00 a.m., this time louder and longer than before, “with the thump and crump and muttering finality of a massive coup de grâce.”

The next day the truth was revealed. Confederate General John Bell Hood, leading the Confederate forces defending Atlanta, had found his main supply line cut off and had ordered that his own munitions train be blown up so that it would not fall into Union hands. In a massive self-destruction that helped cover their retreat, the Confederates torched five locomotives and eighty-one railroad cars full of their own ammunition. This was the sound that Sherman and his men heard. It was the night of September 1, 1864.

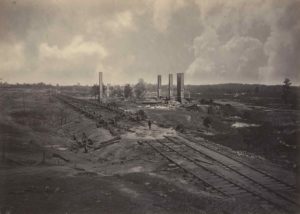

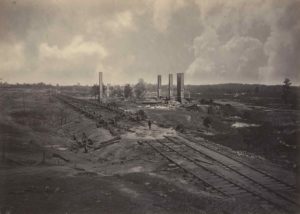

Within days, Sherman’s official campaign photographer George Barnard was at the scene of the explosions. Accompanying Sherman and his men on their destructive march from Nashville to Charleston, Barnard would ultimately assemble sixty-one of his large wet-collodion plates into a deluxe publication, Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, published in New York in 1866. Destruction of Hood’s Ordnance Train is plate 44 (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. G. Barnard, Destruction of Hood’s Ordnance Train, 1864

At the center of the photograph stands a lone man (fig. 2). We cannot tell who he is—the title does not identify him. Likely he is a civilian, a figure exempted from military ritual and allowed a place of solitude. Back to us, clad in dark clothes, he is a man of shaken contour, either slightly aquiver in the breeze or impatient with having to stand still during the exposure, or both. His feet make a wispy fishtail pattern. One imagines him as an associate of the photographer who has walked from Barnard’s position, down the trash-strewn hilly foreground at lower left, further down the gulley at the foot of the hill, and up onto the rail bed, where he could respond to the photographer’s commands about where to stand and for how long. He is within hailing distance.

The man stands within a circle of soot. Although the circle may not have been the epicenter of the explosions, the missing track suggests that the nature of the fire here was different than the one further in the distance. So do the sideways-flung rail carriage wheels to the left of the soot. Further back, the wheels still sit on the rails, implying that there the blaze consumed the wooden cars in steady flame. But nearer to our vantage, in the circle of ash where the lone man stands, a huge detonation likely blew things sideways and burned extra hot. Barnard’s photograph shows a flat volcano. The man is at the crater, at ground zero.

Fig. 2. Barnard. Destruction … (detail)

Standing there, the man seems to verify what happened. Like a journalist, he is on the spot, the embers barely cooled. Following the uncertainty of those cataclysmic sounds—the booms that awakened and disturbed Sherman and his men—the lone man confirms the truth of Hood’s defeat. Standing on the ash imprints the reportorial truth of the scene as much as the light hitting the photographic plate. The weightiness of the shadowed man, even if he flutters unsteadily, surpasses the conjecture of an artist’s drawing of a few weeks later that shows the exploding ammunition train. Unlike the fabulist with his pencil, the photographer and his associate occupy the actual scene, letting it be stamped on them, a predicate of there-ness and truthfulness.

The verification was timely. A few days earlier, George B. McClellan had accepted the Democratic Party’s nomination for president, running on the party platform that the North should sue for peace with the South and end the war, slavery intact. A cartoon by Thomas Nast, appearing in Harper’s Weekly on September 3, 1864, shows the disastrous implications of such a peace: a defeated Union soldier, his sacrifice a waste, slumps to shake hands with a triumphant Jefferson Davis. “One party seems to want peace,” wrote Major Connolly to his wife, ending the same letter in which he had described hearing the explosions. “That suits us here. We want peace too, honorable peace, won in the full light of day, at the cannon’s mouth and the bayonet’s point, with our grand old flag flying over us as we negotiate it, instead of cowardly peace purchased at the price of national dishonor.”

Barnard’s photograph, taken in those same days, says that Atlanta is taken, that Sherman is victorious, and that the war needs to be fought to its conclusion. The proof is in the photographic glass, in the stone and rail and wood, and in the man at the center of the ash. Neither black nor white (it is impossible to tell his race), he solemnly acknowledges the massive destruction of the southern war machine and makes the case implicitly for more of the same violence as the only way to bring peace. In Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, true enough, there will be many scenes of obliteration still to come after the Destruction of Hood’s Ordnance Train. Relentlessly, the rebellion will be flattened to the ground. When it is not flattened, picturesque windows will be left in its broken walls only so that the viewer can examine how little of the defeated place still exists. On September 12, Sherman wrote to the mayor of Atlanta, who had implored him to stop bombarding the city: “You might as well appeal against the thunder storm as against these terrible hardships of war.”

But the solitary man goes beyond the news cycle. Four prominent chimneys repeat his upright form, multiplying his solitude and extending it to the heavens. He stands before these chimneys like a shepherd before the columns of a ruined Roman temple in the romantic paintings that Barnard admired. The Old South, the photograph says, is a fallen empire, a ruined civilization. But the chimneys also lift the man into the skies, as if he were part of the black smoke that once emanated from this building, an iron mill destroyed in the explosions. Organizing his photograph not just so that the lone man would be at the center, but so that the chimneys would rise into the clouds, Barnard aligns the man’s contemplation not just with the events of the day but with an eternal churn of time. That Barnard “combination printed” the clouds from another negative—his photograph would otherwise show the sky only as a blank gray—creates the image’s mysteriously otherworldly sky and the lone contemplator’s relation to it. The windswept and light-stained clouds come not only from another negative but seemingly from another world, as if a passing planet had allowed Barnard to borrow its atmosphere. They rhyme with the flutter of the man’s black coat and trousers, the shifting of his knees. The sky’s main echo on the ground is the soot on which he stands, a flattened cloud of cinders that resembles the heavens’ light gray. The lone man courses with a rhythm of sun and cloud, the full flow of romantic history—empires rising and falling but also some otherworldly time, some timeless time—that the historian internalizes within his own small body.

Standing there, the man aligns with not just flow but frozenness. The diagonal of the tracks implies far-off movement, but no trains will run on them for some time. Where the blast was, where he is, time has stopped. The historian pauses at the location where the momentum of events ceases. There the motionless wheel-carriages suggest the arrested force of his own observations. The massive mill wheel between the chimneys has likewise run into the ground. Aligned to these signs, the historian likewise freezes the action of the day—like the photographer, he keeps the world from rolling. Their mutual hope is that in stillness the significance of an event will become cryptically clear. The earth itself still turns, the clouds still scud across the sky, but the historian feels no contradiction. In Barnard’s romantic view, the historian feels the fixation of a moment in time and the relation of that moment to eternity. The lone man’s shadow looks like an oil stain on the soot, but it also charts the path of the sun.

It is proper that all this destruction leaves a lasting mark on the historian. He does not glide by the scene of violence, even if his presence there is of short duration. Rather, like the photographer’s plate, he allows the scene to imprint itself on him. To his dying day he will retain the record of what he saw. Even if he forgets his place, losing the memory of having stood on the tracks, the place will not forget him. It will be in his consciousness like a possession buried in the earth, like the belongings that the citizens of Atlanta interred for safekeeping as they departed the city. Even if he forgets that it was him in the photograph, remembering only that he actually stood beneath a pastel-blue sky on that spot or, conversely, if his presence in the photograph is all that he recalls, the pastel-blue sky having been forgotten, the confusion of experiences will not dissipate his sense of having been there. Transfer the man to a heady scene of Broadway in New York, bright on a summer’s day, with everyone else happy and prancing beneath parasols and top hats, and he would still walk in the cloud of his shaken contours.

Damage, to judge by the photograph, is the historian’s proper element. Barnard’s contemporary J. T. Trowbridge wrote of looking out a railway car window in Atlanta on a rainy morning just after the war, seeing the “windrows of bent railroad iron by the track; piles of brick; a small mountain of old bones from the battle-fields, foul and wet with the drizzle; a heavy coffin-box, marked ‘glass,’ on the platform, with mud and litter all around.” Trowbridge let the sights impress him, then wrote liquid descriptions that impress the reader. In the same way, Barnard’s sole observer becomes a photographic plate, allowing the grit of the sand and clay and pebbly wasteland to imprint itself on him until he, too, sensitively registers the scene. The pathological stillness of his contemplation registers the aftershocks of violence as only a slight fluctuation in his trembling clothes. Alone, he keeps the landscape from breaking apart.

It is a depressing scene, even if it shows the demise of the Confederacy. The photograph has all the hallmarks of a victory parade except the people and the motion and the joy. What, if anything, redeems the emptiness?

My own answer is imagination. Adrift in the wasted world, either the historian traces the wreckage, speaking in a voice of dejection and outrage, or the historian can invent from those same woebegone feelings. In the latter case, something new emerges from the destruction and violence. That something new is not an asinine version of progress—of forward-looking and backward-forgetting. It is always committed to the recollection that allows it to come into being. Instead of flying away, the historian’s invention owes allegiance to the particular topography in which it finds itself. Down every gulley, across each desolate rock pile and sandpit, the imagination must trace its way, divagating the broken tracks, stumbling down the shallow hillsides, taking an exact impression at each point of what is not itself. The imagination works like lava, flowing across the terrain, making a mold of what it streams over. The imagination clamps to memory like Barnard’s sky to the earth. The imagination depicts unbelievable things—it is imported from other scenes, “combination printed” into a first picture in which it does not belong. Yet somehow it does belong. And it makes us look again, and look longer, at a photograph we might barely have noticed otherwise.

What does the imagination trace in Destruction of Hood’s Ordnance Train? The answer will be different for each viewer. I can give only my own account. Improbably, I imagine the photograph as a story of love. I say this because General John Bell Hood, the commander who ordered that the ordnance train be blown up, was deeply in love at the time. Continue reading …

How is something that is not there still present in a photograph? What is the importance of seeing a photograph in this way? Looking at George Barnard’s Civil War photograph Destruction of Hood’s Ordnance Train, this essay meditates on the operations of imagination in historical images.

ALEXANDER NEMEROV gave the sixty-sixth annual Andrew W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts at the National Gallery of Art this past spring. His most recent book, Soulmaker: The Times of Lewis Hine, published in 2016, was short-listed for the 2017 Marfield Prize/National Award for Arts Writing.

ALEXANDER NEMEROV gave the sixty-sixth annual Andrew W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts at the National Gallery of Art this past spring. His most recent book, Soulmaker: The Times of Lewis Hine, published in 2016, was short-listed for the 2017 Marfield Prize/National Award for Arts Writing.

The topic of counterfactual histories has engaged Catherine Gallagher for some time. In addition to the essays in this new book, her “When Did the Confederate States of America Free the Slaves?” was published in the special forum Counterfactual Realities in Representations 98, and “The Formalism of Military History” appeared in our 25th anniversary special issue On Form.

The topic of counterfactual histories has engaged Catherine Gallagher for some time. In addition to the essays in this new book, her “When Did the Confederate States of America Free the Slaves?” was published in the special forum Counterfactual Realities in Representations 98, and “The Formalism of Military History” appeared in our 25th anniversary special issue On Form.

JONATHAN KRAMNICK

JONATHAN KRAMNICK

We all know that we have feelings when we encounter works of art. We laugh, we cry. We feel pity and fear. We like and we dislike. We shudder and shiver and tingle. We are amused, delighted, thrilled, teary, bored, relaxed, turned on, horrified, enraged, surprised, depressed, embarrassed, shocked, and fascinated. We know that these “aesthetic” feelings constitute one of the primary values of art as such, and that the problem of how to analyze and evaluate these feelings is one of the basic problems of aesthetic theory, at least since Plato worried about the way poets affected their audiences in The Republic. Many of our fundamental aesthetic categories—tragedy and comedy, the beautiful and the sublime—have become fundamental because they offer ways to think about how art affects its audiences.

We all know that we have feelings when we encounter works of art. We laugh, we cry. We feel pity and fear. We like and we dislike. We shudder and shiver and tingle. We are amused, delighted, thrilled, teary, bored, relaxed, turned on, horrified, enraged, surprised, depressed, embarrassed, shocked, and fascinated. We know that these “aesthetic” feelings constitute one of the primary values of art as such, and that the problem of how to analyze and evaluate these feelings is one of the basic problems of aesthetic theory, at least since Plato worried about the way poets affected their audiences in The Republic. Many of our fundamental aesthetic categories—tragedy and comedy, the beautiful and the sublime—have become fundamental because they offer ways to think about how art affects its audiences. JONATHAN FLATLEY

JONATHAN FLATLEY