Pain and Memory in the Formation of Early Modern Habitus

by Mitchell Merback

The essay begins:

No amount of contextualizing or revision, it seems, will ever free the European Middle Ages from its reputation as an era overcome by social and religious violence, riven by conflicts and cruelties, accustomed to the sight of death, poor in hygiene and other forms of self-care, and possessed of a devotional culture deliriously intimate with pain. Long central to the idea of the premodern as Other, this dreamlike historical image was once dubbed by Umberto Eco the “shaggy” Middle Ages. Its leitmotifs are the presumed plenitudes of violence and pain as well as contemporary attitudes toward them. Inhabitants of this medium aevum, the “shaggy” narrative tells us, did not labor under the neurotic need to eliminate bodily pain but accepted it as a fact of life and, indeed, celebrated it as useful on the path to salvation. Physicians and confessors alike understood pain in this way—as essentially therapeutic—so medieval culture in general, we hear, was not pain-averse but quite the opposite, “philopassianic,” to use a recent scholarly coinage.

As far as medieval-modern comparisons go, this one concerning attitudes toward pain is probably as good as any other; but to take it any further requires making two fundamental distinctions, both of which will be important to the theme of this paper, which is the interdependence of memory training and pain in the formation of an early modern habitus. The first of these is the distinction between pain thresholds and pain tolerances. Pain thresholds are best regarded as neurobiological facts of the species, part of a “hardwiring” that changes little over time (early in the twentieth century, for instance, Charles Sherrington defined pain experiences in terms of nociception, as the “psychical adjunct of a protective reflex”). Pain tolerances are something far closer to cultural products, variable and largely determined by group values and narratives, cultural practices, and the whole ecology of social life. We can be fairly certain that the majority of medieval people, living under conditions that produced an array of ailments and physical discomforts, developed pain tolerances higher than ours in the modern era. Accounting for this difference requires that we attend to the complex conceptualization of pain as both a primary “sensation”—if not the paradigmatic form of individual sensation—and a “hybrid emotion,” that is, an emotion that merges otherwise distinct affective states and modalities of response. And that, in turn, requires us to think in terms of the symbolic significance of human suffering wherein it holds to a positive purpose or end, as well as the degree to which it then stands open to whatever agencies of consolation, therapy, and cure a culture can make available to its members at a given time. Viewed in this biocultural light, medieval Christians appear to have approached pain as any other stratified cultural group would do: they attended to it, worked to alleviate its excesses, and furnished certain members with codes for conceptualizing and communicating what would otherwise be a wholly subjective, internal experience. Such codes and norms translated into more or less conventionalized “scripts” for pain behavior. Through such cultural conventions medieval culture succeeded, at least notionally, in stabilizing pain’s significance—taming and harnessing its uniquely “world-destroying” powers—thus rendering it productive for individuals and groups.

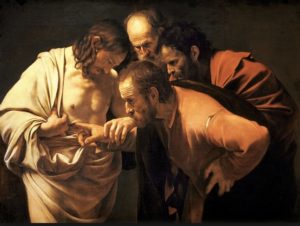

Trying to understand pain tolerances as a symptom of culture already gets us entangled in a second distinction: that between pain experiences and pain expressions. Here we enter upon a field of investigation in which the historian of art feels right at home, since questions surrounding the representation of pain in the visual arts have always been part and parcel of imitative art’s charge to represent psychic states and moral virtues—or their opposites—through coded bodily movements, gestures, and physiognomic signs. But questions of pathetic naturalism only get us so far in explaining why, for example, the famous clenched brow of the Trojan priest Laocoön in the eponymous figure group in Rome, as a physiognomic token of pain, communicated to its beholders a “pain-experience” so different from the one conveyed by its counterpart in the Master of Flémalle’s image of a Crucified Thief. We could rehearse the clichéd contrast between heroic death in pagan tragedy and sacrificial suffering in Christian theology to see that distinct narratives of human suffering and conflict are what drive the transferences between pain experiences, pain representations, and pain perceptions. Would we find that it is the very possibility of narrative that makes pain culturally intelligible in the first place? What’s clear is that the full implications of a culture’s narrative-ideological meanings for pain expression in the visual arts would be lost if we failed to attend to the situated functions of images, the peculiar agency they are granted to enlist the beholder’s effort in realizing their effects and completing their meanings in historically specific situations of use. Something of the logic of that agency can be recovered and measured by the forms of response demanded and structured by the image. We may begin, then, with one kind of image that, in portraying the very response it demands, tells us something about the peculiar way spectacular pain expressions registered in late medieval culture. Continue reading …

Trying to understand pain tolerances as a symptom of culture already gets us entangled in a second distinction: that between pain experiences and pain expressions. Here we enter upon a field of investigation in which the historian of art feels right at home, since questions surrounding the representation of pain in the visual arts have always been part and parcel of imitative art’s charge to represent psychic states and moral virtues—or their opposites—through coded bodily movements, gestures, and physiognomic signs. But questions of pathetic naturalism only get us so far in explaining why, for example, the famous clenched brow of the Trojan priest Laocoön in the eponymous figure group in Rome, as a physiognomic token of pain, communicated to its beholders a “pain-experience” so different from the one conveyed by its counterpart in the Master of Flémalle’s image of a Crucified Thief. We could rehearse the clichéd contrast between heroic death in pagan tragedy and sacrificial suffering in Christian theology to see that distinct narratives of human suffering and conflict are what drive the transferences between pain experiences, pain representations, and pain perceptions. Would we find that it is the very possibility of narrative that makes pain culturally intelligible in the first place? What’s clear is that the full implications of a culture’s narrative-ideological meanings for pain expression in the visual arts would be lost if we failed to attend to the situated functions of images, the peculiar agency they are granted to enlist the beholder’s effort in realizing their effects and completing their meanings in historically specific situations of use. Something of the logic of that agency can be recovered and measured by the forms of response demanded and structured by the image. We may begin, then, with one kind of image that, in portraying the very response it demands, tells us something about the peculiar way spectacular pain expressions registered in late medieval culture. Continue reading …

Describing the essay, the author writes: “Between the Middle Ages and Early Modern period, pain and memory became interdependent in three domains of social and religious life: religious devotion, education, and criminal justice. The grounds for this affiliation were prepared by a training of individuals in the control of affect and the acceptance of memory training as a regimen of virtual self-wounding, often facilitated by violent imagery. Across the three domains examined here, Christian subjectivity was quietly reformed and an embodied habitus inculcated to meet the demands of an age no longer anchored in unquestioned truths.”

MITCHELL MERBACK is the Arnell and Everett Land Professor in the History of Art at Johns Hopkins University. His most recent book is Perfection’s Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Dürer’s “Melencolia I” (Zone Books, 2017). Current projects include a reevaluation of the European tradition of the identification portrait and a study of tragic recognition as theme and metatheme in Christian art before 1500.

MITCHELL MERBACK is the Arnell and Everett Land Professor in the History of Art at Johns Hopkins University. His most recent book is Perfection’s Therapy: An Essay on Albrecht Dürer’s “Melencolia I” (Zone Books, 2017). Current projects include a reevaluation of the European tradition of the identification portrait and a study of tragic recognition as theme and metatheme in Christian art before 1500.

“The essays collected here counter [the] fantasy of pain as a knowable sensation that lies within that is then represented, or misrepresented, in language. Instead, they consider pain as always already enmeshed in social life, and representation as the means through which we can engage this imbrication. In so doing, they demonstrate the importance of bringing together two approaches to the problem of pain that have often been kept distinct. The first is the anthropological insight that pain behavior constitutes a mode of social engagement and, hence, that suffering is necessarily bound up with shifting, often unpredictable, cultural, familial, and interpersonal dynamics. The second involves a historical and literary-critical account of representation’s complex and productive relations to both experience and culture.” –from the editor’s introduction

“The essays collected here counter [the] fantasy of pain as a knowable sensation that lies within that is then represented, or misrepresented, in language. Instead, they consider pain as always already enmeshed in social life, and representation as the means through which we can engage this imbrication. In so doing, they demonstrate the importance of bringing together two approaches to the problem of pain that have often been kept distinct. The first is the anthropological insight that pain behavior constitutes a mode of social engagement and, hence, that suffering is necessarily bound up with shifting, often unpredictable, cultural, familial, and interpersonal dynamics. The second involves a historical and literary-critical account of representation’s complex and productive relations to both experience and culture.” –from the editor’s introduction