Staging the Last Judgment in the Trial of Charles I

by Julie Stone Peters

The essay begins:

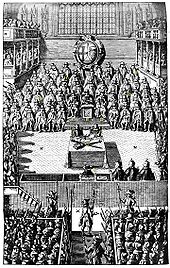

On the morning of January 9, 1649, Sergeant-at-Arms Edward Dendy rode into Westminster Hall, surrounded by an entourage of officers and followed by six trumpeters on horseback, with more than two hundred Horse and Foot Guards behind them. Drums beat in the Old Palace Yard, the trumpeters sounded their horns in the hall, and the crier announced the “erecting of an High Court of Justice, for the trying and judging of Charles Stuart King of England.” Eleven days later, the two great gothic doors opened to a space transformed. The trial’s managers had torn out the hall’s ramshackle barriers and the booksellers’ and milliners’ booths that lined its walls and constructed a central raised stage flanked by galleried boxes, whose decorative columns supported balconies fronted by ornately carved balustrades. They had spread Turkish carpets on the tables and platforms and hung yards and yards of scarlet draperies from the elevated seating at the back of the stage. And they had built, at the center, a three-tiered dais with a trio of armchairs, the furniture adorned in gold-fringed, tasseled crimson velvet and studded with precious metals. Into this magnificently appointed space marched several hundred guards bearing brilliantly gilded “rich partizans” and “javelins” decorated “with velvet and fringe.” With them was the sergeant-at-arms, holding aloft the great golden mace of the House of Commons, and behind him a sword bearer carrying the Sword of State brought from the Westminster Jewel Tower. Those in charge had issued an order: even outside the precincts of the court, the presiding judge was to be referred to only by his new title: “Lord President of the High Court of Justice.” As the sixty-seven commissioners serving as judges ascended to their scarlet-draped seats, the “Lord . . . of the High Court,” in a “black Tufted Gown” with an inordinately long train (carried by an entourage of attendants), paraded toward his dais amidst the sea of begilded and velvet-fringed javelins. This was hardly the austere mise-en-scène one might expect from the “godly Puritans” who had mounted their coup d’état and put their king on trial—in part, at least, in the name of stamping out ceremonial idolatry and the gaudy pomp of the vainglorious Stuarts.

On the morning of January 9, 1649, Sergeant-at-Arms Edward Dendy rode into Westminster Hall, surrounded by an entourage of officers and followed by six trumpeters on horseback, with more than two hundred Horse and Foot Guards behind them. Drums beat in the Old Palace Yard, the trumpeters sounded their horns in the hall, and the crier announced the “erecting of an High Court of Justice, for the trying and judging of Charles Stuart King of England.” Eleven days later, the two great gothic doors opened to a space transformed. The trial’s managers had torn out the hall’s ramshackle barriers and the booksellers’ and milliners’ booths that lined its walls and constructed a central raised stage flanked by galleried boxes, whose decorative columns supported balconies fronted by ornately carved balustrades. They had spread Turkish carpets on the tables and platforms and hung yards and yards of scarlet draperies from the elevated seating at the back of the stage. And they had built, at the center, a three-tiered dais with a trio of armchairs, the furniture adorned in gold-fringed, tasseled crimson velvet and studded with precious metals. Into this magnificently appointed space marched several hundred guards bearing brilliantly gilded “rich partizans” and “javelins” decorated “with velvet and fringe.” With them was the sergeant-at-arms, holding aloft the great golden mace of the House of Commons, and behind him a sword bearer carrying the Sword of State brought from the Westminster Jewel Tower. Those in charge had issued an order: even outside the precincts of the court, the presiding judge was to be referred to only by his new title: “Lord President of the High Court of Justice.” As the sixty-seven commissioners serving as judges ascended to their scarlet-draped seats, the “Lord . . . of the High Court,” in a “black Tufted Gown” with an inordinately long train (carried by an entourage of attendants), paraded toward his dais amidst the sea of begilded and velvet-fringed javelins. This was hardly the austere mise-en-scène one might expect from the “godly Puritans” who had mounted their coup d’état and put their king on trial—in part, at least, in the name of stamping out ceremonial idolatry and the gaudy pomp of the vainglorious Stuarts.

When the Rump Parliament brought Charles to Westminster Hall in 1649, no reigning monarch had ever before been subjected to a public trial. The unprecedented step of staging the trial publicly was, of course, a bid to legitimize the overthrow (or at least shackling) of the monarchy through the appearance of legality and public consensus. The Parliament that had voted to try Charles consisted only of those who remained after a radicalized army had forcibly barred moderate members from entering the House of Commons and abolished the House of Lords. The Westminster Hall setting would help quell doubts about the trial’s legality. To hold such a trial in Westminster Hall was to appear to follow the long line of parliamentary trials that had been held there, and to remind the public of Parliament’s ancient judicial power. Moreover, Westminster Hall stood for principles of transparency and public accountability. Those in charge (said Colonel Thomas Harrison) despised cloak-and-dagger “privat[e] violence” and all such “base and obscure undertakings.” The largest public space in England (with a capacity of thousands), Westminster Hall had been chosen (the principal Parliamentary newspaper declared) because it was “a place of publicke resort, . . . the place of the publicke Courts of Justice for the Kingdome.” There, all would be “open, and to the eyes of the world,” and “all persons without exception, desirous to see, or hear” would be welcome: rich or poor, merchant or gentry, Presbyterian, Independent, Leveller, or even Royalist. The trial would represent the English people as a whole: the very body in whose name the court had come into existence.

Scholars have largely accepted this political account, explaining away the trial’s elaborate ceremonialism (usually mentioned only in passing, if at all) as a transparently straightforward attempt to strengthen its bid for legitimacy. But a political analysis does not fully account for either the grandiosity of the trial or the details of its unorthodox staging. One of the central goals of the religious radicals who put Charles on trial was in fact the elimination of spectacular rituals, Popish images, vestments, ornaments, and other “Idols of the Theatre” from churches, court, entertainment venues, and other public places. Why did the men who planned the trial’s staging and effects, mostly fervent iconoclasts wary of spectacular display and committed to visual sobriety and frugality, spend so much time and money on staging the trial as an elaborately theatrical, magnificently appointed, outrageously costly ritual (gorgeous vestments and all), when such a spectacle would appear to violate some of the most important principles for which they stood?

Unlike previous scholars (who have largely focused on the trial’s legality, its political consequences, or its literary and visual representation), I attempt to answer this question by focusing on the visual and visceral unfolding of the trial itself, looking closely at spatial arrangements, icons, and scenic configurations in order to explore the theological meaning of its densely symbolic, visual, gestural, sartorial, iconographic, and aural staging. When I describe Charles’s trial, or other legal events and practices, as theatrical, I mean two related things: first, that they draw on techniques not exclusive to but elaborately developed in the institutional theater; second, that contemporaries often identified such events and practices as theatrical, through a highly inflected constellation of terms that associated them with the institutional theater and related forms of enacted entertainment (spectacle, show, tragedy, stage tricks, and more). These terms and the attitudes they convey both shaped and reflect the meaning of the events they describe and are key to understanding them. Continue reading …

The trial of Charles I (said mid-seventeenth-century radical Protestants) was “a Resemblance and Representation of the great day of Judgement.” Situating the trial in its theological and iconographic context, viewing it as an expression of broader Puritan performance culture, this essay offers a close reading of its staging, arguing that we should view the assertion that the trial resembled Judgment Day not as an abstract theological aspiration but as a concrete description of the trial’s visual, spatial, and dramatic representation of the Last Judgment.

JULIE STONE PETERS is the H. Gordon Garbedian Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, where she teaches on a range of topics in the humanities, from drama, film, and media to law and culture. Her most recent book is Theatre of the Book: Print, Text, and Performance in Europe 1480–1880. She is currently working on a historical study of legal performance.

JULIE STONE PETERS is the H. Gordon Garbedian Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, where she teaches on a range of topics in the humanities, from drama, film, and media to law and culture. Her most recent book is Theatre of the Book: Print, Text, and Performance in Europe 1480–1880. She is currently working on a historical study of legal performance.

Hear Pulitzer Prize-Winning Writer HILTON ALS

Hear Pulitzer Prize-Winning Writer HILTON ALS

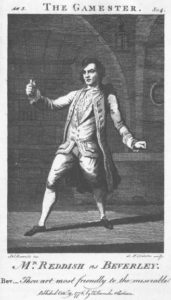

In 1778, Samuel Johnson was asked to weigh in on the prose of a new bourgeois tragedy, The Female Gamester. Its author, Gorges Edmond Howard, was a Dublin-based lawyer and literary dabbler whose attempt at domestic drama might have been wholly forgotten were it not for the fragment of Johnsoniana he preserved in its preface. Having originally written the play in a mixture of prose and verse, Howard had been advised by “several of [his] literary acquaintance” that his “not much exalted” prose was much more suitable to the “scene . . . laid in private life, and chiefly among those of middling rank.” For many, it seems, the bourgeoisie suffered in prose. But Johnson, Howard recalls, would have none of this:

In 1778, Samuel Johnson was asked to weigh in on the prose of a new bourgeois tragedy, The Female Gamester. Its author, Gorges Edmond Howard, was a Dublin-based lawyer and literary dabbler whose attempt at domestic drama might have been wholly forgotten were it not for the fragment of Johnsoniana he preserved in its preface. Having originally written the play in a mixture of prose and verse, Howard had been advised by “several of [his] literary acquaintance” that his “not much exalted” prose was much more suitable to the “scene . . . laid in private life, and chiefly among those of middling rank.” For many, it seems, the bourgeoisie suffered in prose. But Johnson, Howard recalls, would have none of this: