An Ecology of Operations: Vigilance, Radar, and the Birth of the Computer Screen

by Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan

The essay begins:

Computer screens emerged from the problem of integrating humans, computers, and their environment in a single problem-solving system. More specifically, digital graphics and computerized visualization emerged from the problem of integrating real-time human feedback into computerized radar systems developed by the US military in the early decades of the Cold War.1 In the course of the 1950s and 1960s tinkering engineers adapted techniques developed for visualizing enemy trajectories to somewhat less bellicose applications in computer graphics. Indeed, a wide variety of early computer-generated graphics—from John Whitney’s computer-aided animations and Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad program to early video games like Spacewar! and Tennis for Two—did little more than tweak the techniques of aerial defense into diversions like visualizing abstract patterns and intercepting, so to speak, an opponent’s tennis ball. To borrow film historian Kyle Stine’s felicitous phrasing, by folding picturing and calculation into dual aspects of a single process, these systems joined humans and calculating instruments in a single circuit of information processing. In fire-control systems (as mechanically aided approaches to tracking and targeting the enemy are often called), these feedback circuits often included the environment itself. Together, these elements of the system—human, instrument, environment—formed what I term an ecology of operations that distributed complex mathematical problems in recursive chains.

Computer screens emerged from the problem of integrating humans, computers, and their environment in a single problem-solving system. More specifically, digital graphics and computerized visualization emerged from the problem of integrating real-time human feedback into computerized radar systems developed by the US military in the early decades of the Cold War.1 In the course of the 1950s and 1960s tinkering engineers adapted techniques developed for visualizing enemy trajectories to somewhat less bellicose applications in computer graphics. Indeed, a wide variety of early computer-generated graphics—from John Whitney’s computer-aided animations and Ivan Sutherland’s Sketchpad program to early video games like Spacewar! and Tennis for Two—did little more than tweak the techniques of aerial defense into diversions like visualizing abstract patterns and intercepting, so to speak, an opponent’s tennis ball. To borrow film historian Kyle Stine’s felicitous phrasing, by folding picturing and calculation into dual aspects of a single process, these systems joined humans and calculating instruments in a single circuit of information processing. In fire-control systems (as mechanically aided approaches to tracking and targeting the enemy are often called), these feedback circuits often included the environment itself. Together, these elements of the system—human, instrument, environment—formed what I term an ecology of operations that distributed complex mathematical problems in recursive chains.

In the pages that follow I term this integration of visuality, calculation, territory, human problem-solving, and the human body in early information processing computational screening. At the most basic level, this term designates the productive integration of visualization technologies (that is, screen displays) and information processing (the screening and filtering of incoming data) that gave birth to digital graphics. Frequently, the screening of space (the flow of bodies across the membrane of a territory or through a battlefield) is also a key element of computational screening. As an analytical concept, computational screening calls attention to the history of computers as what Gilbert Simondon termed an “open machine,” reliant on continuous exchange with humans and their physical environment. In computational screening, visual, graphical, and optical media, as well as physical space and human bodies, collaborate in the production of circuits of computation. Although computational screening took shape in the complex human-computer systems of twentieth-century fire-control, today it includes a much wider array of problems involving conditions too complex to permit problem solving by computing machines alone (that is, without human support). The processing of crunchable social data by Facebook and the monitoring of traffic patterns by the navigation app Waze, for example, involve the development of sophisticated visual interfaces that entice humans to complete information processing tasks too complex for digital instruments alone. Indeed, the actualization of computers into something approaching Alan Turing’s universal machines is inconceivable without a vast array of visual interfaces that permit computers to enter into dynamic feedback loops incorporating input from users and their environments. Without the digital images enabling this circuit, the computer is little more than a fantastic automaton: that is, either an inert and preprogrammed bauble or a plaything that dwells in the imagination.

This article reconstructs a history of computational screening as it developed from naval artillery control systems developed just after World War II through the deployment of the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) computerized radar defense system shortly before the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. This historical arc emphasizes how the demands that modern warfare placed upon vision, territory, and attention in this period produced not only a new kind of digital image but also, specifically, a new kind of interactive image: one that enlisted bodies, attention, and calculation in the production of space. As art historian Pamela Lee has incisively written, “Cold War defense strategy could itself be described as a semiotic endeavor—an attempt to decode a shadowy enemy through a raft of signs both militaristic and cultural, including ‘indexical’ traces registered through the new technologies of radar; anthropological analyses of Soviet, Japanese, and German attitudes to authority; and the interactive dynamics observed within the ascendant field of the behavioral sciences.” I track one of these semiotic endeavors, the development of computational screening, an enterprise that drew on radar, computer science, psychology, moving images, physiology, geography, and other fields to establish a martial aesthetic that informs the attention economies of twenty-first-century digital cultures.

This history of computational screening and its alliance of visual interfaces with information processing reframes a much-discussed problem concerning vision and computing. Frequently, theorists of media and visual culture have argued that the computer is not a visual device. Media theorist Friedrich Kittler posited that in an age of electronic screens “visible optics must disappear into the black hole of circuits . . . [because] computers, as they have existed since World War II, are not designed for image-processing at all.” Germanophone media theorists Wolfgang Hagen and Claus Pias echoed Kittler, resolutely declaring in their respective theoretical sallies that “there is no digital image.” These and a host of other digital iconoclasts argue that, unlike traditional media such as photography, cinema, or painting that have a more or less determinate relationship to light, color, and spatial extension, electronic signals have neither a fixed nor an intrinsic relationship to vision. Often these theorists further maintain that the digital image lacks stable relationships to human bodies and space. For the proponents of digital iconoclasm, electronic pictures are like the afterimages that flicker into perception after the severing of an optical nerve: They may “look” like the real thing but they are the tricks of habituation, bereft of any correspondence beyond the random flickering of electrical signals. Continue reading …

Image: Spacewar! running on the Computer History Museum’s PDP-1. Photo: Joi Ito

In this essay Bernard Geoghegan examines the birth of interactive computer screens from enemy targeting and tracking systems (especially computerized radar) that distributed information processing in an ecology of operations among humans, computational instruments, and the environment. He proposes a concept of “computational screening” to account for the integration of visualization and information processing that gave rise to digital images.

BERNARD DIONYSIUS GEOGHEGAN is a media theorist, historian of technology, and occasional curator. He teaches at the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London and can be reached online at www.bernardg.com or via Twitter at @bernardionysius.

BERNARD DIONYSIUS GEOGHEGAN is a media theorist, historian of technology, and occasional curator. He teaches at the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College London and can be reached online at www.bernardg.com or via Twitter at @bernardionysius.

Michael Lucey

Michael Lucey Milan, 19 November 1969, noon. In the heart of the city center, on the streets surrounding the Duomo, two crowds converge. The first, a large group of union workers, is gathered in the Teatro Lirico—there is a general strike all over Italy, the grievance being a rise in the cost of housing. A second group, an assortment of extra-parliamentary left-wing organizations whose Italian crop was in full flourish by 1968, is marching down Via Larga. Since the Teatro Lirico is also on Via Larga, the workers leaving their assembly mingle with the other demonstrators. The crowd swells and heaves. The police intervene. After a few moments, the scene has degenerated: the police, in vans, move toward the demonstrators; the demonstrators find steel tubes in a nearby building site and use them as weapons. A police officer driving one of the vans—Antonio Annarumma—dies in the struggle, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day.

Milan, 19 November 1969, noon. In the heart of the city center, on the streets surrounding the Duomo, two crowds converge. The first, a large group of union workers, is gathered in the Teatro Lirico—there is a general strike all over Italy, the grievance being a rise in the cost of housing. A second group, an assortment of extra-parliamentary left-wing organizations whose Italian crop was in full flourish by 1968, is marching down Via Larga. Since the Teatro Lirico is also on Via Larga, the workers leaving their assembly mingle with the other demonstrators. The crowd swells and heaves. The police intervene. After a few moments, the scene has degenerated: the police, in vans, move toward the demonstrators; the demonstrators find steel tubes in a nearby building site and use them as weapons. A police officer driving one of the vans—Antonio Annarumma—dies in the struggle, in circumstances that remain unclear to this day. DELIA CASADEI

DELIA CASADEI In this a bold new account of how celebrity works, Marcus draws on scrapbooks, personal diaries, and vintage fan mail to trace celebrity culture back to its nineteenth-century roots, when people the world over found themselves captivated by celebrity chefs, bad-boy poets, and actors such as the “divine” Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), as famous in her day as the Beatles in theirs.

In this a bold new account of how celebrity works, Marcus draws on scrapbooks, personal diaries, and vintage fan mail to trace celebrity culture back to its nineteenth-century roots, when people the world over found themselves captivated by celebrity chefs, bad-boy poets, and actors such as the “divine” Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), as famous in her day as the Beatles in theirs.

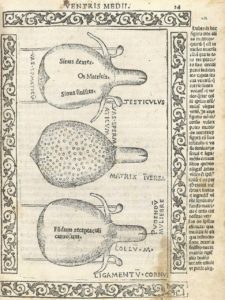

“Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume.

“Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume. BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century.

BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century.