by Boyd Brogan

The essay begins:

“Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume.

“Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume.

More recent studies have reached the same conclusion as de Certeau from a different and more strictly historicist angle. Nancy Caciola and Moshe Sluhovsky both agree that possession was linked to femininity but trace this link to premodern medical concepts of gender rather than twentieth-century psychiatric ones. Yet the assertions of these historicist scholars are interestingly close to those of the psychoanalytic studies that preceded them. Sluhovsky’s claim “The history of possession is a history of bodies. . . . It is therefore inevitably a gendered history” echoes the program of Roper’s provocatively titled Oedipus and the Devil: to investigate “the irrational and unconscious . . . the body . . . and the relation of these two to sexual difference.” Both assume that a history of the body must be a history of what Roper calls “the physiological and psychological reality” of gender.Similarly, it seems no great leap from the “porosity” and “openness” that Caciola finds in medieval female anatomy to Steven Connor’s Lacanian association of possession with “invaginated hollowness” and cultural perceptions of “the castration or deficiency of the female body.”

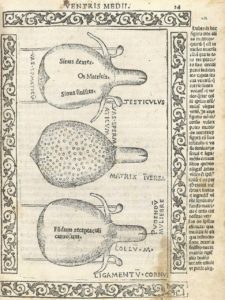

A similar trend has been apparent in medical historiography. Much of the most significant work on early modern medicine and the gendered body has been generated by the sustained and hostile reaction against the “one-sex model” propounded in Thomas Laqueur’s Making Sex. After Laqueur sensationally claimed that the premodern era lacked a binary concept of gender, a series of major studies devoted themselves to reassessing, and to some extent rebuilding, the anatomical and physiological premises of early modern sexual difference. Much of this work has focused on medical writings on womb diseases. These scholars have broken with the notion that illnesses of this type can be “retrospectively diagnosed” as hysteria. But they have also, it might be argued, subtly confirmed it, by emphasizing the extent to which the womb was indeed viewed as a potent source of mental and physical illnesses that were unique to women. Since some of these illnesses, such as suffocation of the womb, possessed cultural associations with demonic possession, studies like these offer powerful support for the notion that possession too was a kind of female malady.

This article takes as its starting point a series of early modern exorcisms that challenge these premises. The Denham exorcisms of 1585–86 featured a male demoniac, Richard Mainy, who claimed to have a woman’s illness, the disease known as “suffocation of the womb.” They also included a possessed woman, Sara Williams, who underwent apparently sexualized exorcisms centered around her genitals. These narratives may seem at first sight to confirm the existing scholarly picture: a possessed man feminized by a cross-gendered illness and a woman subjected to a “sexual script.” But early moderns, I suggest, would have read them differently. For them, the possessions of Richard Mainy and Sara Williams would have presented a reminder of the similarities rather than the differences between the sexes, and the different but related kinds of plenitude—sexual, humoral, demonic—that affected both. Continue reading …

In this article Boyd Brogan reconsiders the gendering of the early modern body from the perspectives of exorcism and medicine, challenging the emphasis on sexual difference that has guided a generation of work in both these fields. He argues that even the most recent historicist approaches to early modern possession and illness remain shaped by psychoanalytic interpretations that associate possession with hysteria. The article takes as its starting point the sixteenth-century demoniac Richard Mainy, who claimed to suffer from the gynecological condition known as “suffocation of the womb,” which modern historians have often identified as hysteria. Rather than offering a prescient example of “male hysteria,” Brogan argues that Mainy’s statements about his illness reveal the important historical relationship between suffocation of the womb and other convulsive or “falling” illnesses such as epilepsy. It was this wider category of illnesses, affecting both men and women, that was associated with demonic possession in this period. Both possession and the diseases that resembled it, moreover, were linked to early modern theories of sexual physiology that stressed the similarities rather than the differences between male and female sexuality.

BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century.

BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century.

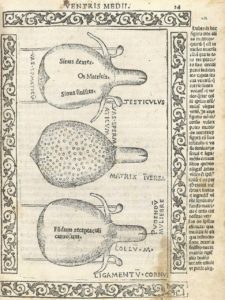

Illustration above: Berengario’s depiction of a uterus in his Isagogae breues, perlucidae ac uberrimae, in anatomiam humani corporis a communi medicorum academia usitatam

It passes for an unassailable truth that the slave past provides an explanatory prism for understanding the black political present. In None Like Us Stephen Best reappraises what he calls “melancholy historicism”—a kind of crime scene investigation in which the forensic imagination is directed toward the recovery of a “we” at the point of “our” violent origin. Best argues that there is and can be no “we” following from such a time and place, that black identity is constituted in and through negation, taking inspiration from David Walker’s prayer that “none like us may ever live again until time shall be no more.” Best draws out the connections between a sense of impossible black sociality and strains of negativity that have operated under the sign of queer. In None Like Us the art of El Anatsui and Mark Bradford, the literature of Toni Morrison and Gwendolyn Brooks, even rumors in the archive, evidence an apocalyptic aesthetics, or self-eclipse, which opens the circuits between past and present and thus charts a queer future for black study.

It passes for an unassailable truth that the slave past provides an explanatory prism for understanding the black political present. In None Like Us Stephen Best reappraises what he calls “melancholy historicism”—a kind of crime scene investigation in which the forensic imagination is directed toward the recovery of a “we” at the point of “our” violent origin. Best argues that there is and can be no “we” following from such a time and place, that black identity is constituted in and through negation, taking inspiration from David Walker’s prayer that “none like us may ever live again until time shall be no more.” Best draws out the connections between a sense of impossible black sociality and strains of negativity that have operated under the sign of queer. In None Like Us the art of El Anatsui and Mark Bradford, the literature of Toni Morrison and Gwendolyn Brooks, even rumors in the archive, evidence an apocalyptic aesthetics, or self-eclipse, which opens the circuits between past and present and thus charts a queer future for black study. Stephen Best is Associate Professor of English at UC Berkeley. His research pursuits in the fields of American and African American criticism have been closely aligned with a broader interrogation of recent literary critical practice. Specifically, his interest in the critical nexus between slavery and historiography, in the varying scholarly and political preoccupations with establishing the authority of the slave past in black life, quadrates with his exploration of where the limits of historicism as a mode of literary study may lay, especially where that search manifests as an interest in alternatives to suspicious reading in the text-based disciplines.

Stephen Best is Associate Professor of English at UC Berkeley. His research pursuits in the fields of American and African American criticism have been closely aligned with a broader interrogation of recent literary critical practice. Specifically, his interest in the critical nexus between slavery and historiography, in the varying scholarly and political preoccupations with establishing the authority of the slave past in black life, quadrates with his exploration of where the limits of historicism as a mode of literary study may lay, especially where that search manifests as an interest in alternatives to suspicious reading in the text-based disciplines.

In this a bold new account of how celebrity works, Marcus draws on scrapbooks, personal diaries, and vintage fan mail to trace celebrity culture back to its nineteenth-century roots, when people the world over found themselves captivated by celebrity chefs, bad-boy poets, and actors such as the “divine” Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), as famous in her day as the Beatles in theirs.

In this a bold new account of how celebrity works, Marcus draws on scrapbooks, personal diaries, and vintage fan mail to trace celebrity culture back to its nineteenth-century roots, when people the world over found themselves captivated by celebrity chefs, bad-boy poets, and actors such as the “divine” Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), as famous in her day as the Beatles in theirs. “Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume.

“Not by chance is the possessed body essentially female,” wrote Michel de Certeau in 1975. Few since have disagreed. Up to the close of the last century, studies of early modern demonic possession were dominated by psychoanalytic perspectives, and it seems fair to say that such perspectives are more than usually likely to produce an association between possession and the female body. Scholars such as John Demos, Lyndal Roper, Robin Briggs, and Steven Connor were no crude Freudians and often preferred Melanie Klein’s emphasis on motherhood to de Certeau’s Lacanian prioritization of language. But they were all working within a tradition, derived ultimately from Freud’s predecessor Jean-Martin Charcot, that viewed possession through the lens of hysteria; and despite regular attempts to extend it to male patients, hysteria remains fundamentally associated with femininity. Since both Freud and Charcot were influenced by their own studies of possession, moreover, the apparently natural “fit” between their theories and these phenomena is less convincing than their advocates sometimes assume. BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century.

BOYD BROGAN is a Centre for Future Health Research Fellow in the Department of History, University of York. He works on sexual abstinence and illness in premodern medicine and on epilepsy, hysteria, and demonic possession from the early modern period to the twentieth century. Hear Pulitzer Prize-Winning Writer HILTON ALS

Hear Pulitzer Prize-Winning Writer HILTON ALS