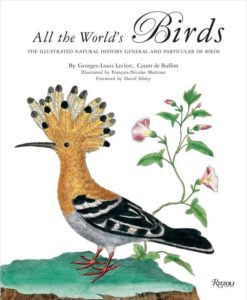

Wildfires to the north of us here in Berkeley, extreme heat just beyond our fog belt, and drought in parts of the globe usually saturated this time of year prompted us to look through our archive for essays that deal in one way or another with views of nature. Among the many relevant pieces, our search revealed a pair of fine-grained essays on the 18th-century naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon:

Noah Heringman’s Deep Time at the Dawn of the Anthropocene argues that the concept of deep time is essential to the intellectual history of the Anthropocene—the name widely (though not yet formally) used for our current geological epoch. Buffon’s Epochs of Nature, one of the earliest secular models of geological time in Enlightenment natural history, uses inscription as a metaphor to mark the advent of biological species, including humans, in the course of earth history. The Anthropocene extends this project of writing ourselves into the rock record. Buffon makes a productive interlocutor for the Anthropocene because he is one of the first to examine climate change and related constraints on human agency in the context of deep time. Heringman examines Buffon’s natural history and associated Enlightenment discourses of primitive art and culture to gain a purchase on the challenges of scale posed by the Anthropocene.

Joanna Stalnaker’s Description and the Nonhuman View of Nature also looks at Buffon, but her focus is in counterpoint to Heringman’s. In her essay, Buffon is discussed in tandem with the poet Jacques Delille, Buffon’s near contemporary, whose innovative practices of description call into question our modern opposition between literature and science, raising the issue of how literature might be transformed through attention to nonhuman views of nature.

Read them together–in the shade if you can find it.