Heideggerian Mathematics: Badiou’s Being and Event as Spiritual Pedagogy

by Ian Hunter

The essay begins:

This paper is an experiment in redescription and reinterpretation. It seeks to take a text that enunciates a Heideggerian metaphysics of the “event”—understood as an encounter in which a subject meets itself emerging from the “void”—and to treat this text itself as an event in a quite other sense: as an ordinary historical occurrence. I will thus be approaching Alain Badiou’s Being and Event historically, in terms of the publication of a written work, but of a highly particular kind. This is a work whose discursive structure programs a refined spiritual pedagogy, and whose composition and reception only make sense within the historical context of the elite academic-intellectual subculture in which this pedagogy operates.

If we consider that Badiou regards his text as a “metaontology” that enunciates the emergence of events and indeed of historical time itself from the domain of nonbeing, then to treat this work as a kind of writing that occurs wholly within a particular historical subculture will imbue our redescription with an indelibly polemical complexion. It should be noted at the outset, however, that this complexion arises from the choice of a particular intellectual-historical method, rather than from any normative contestation of the content of Badiou’s work. This method or stance treats even the most abstract objects of reflection as products of an open-ended array of historical intellectual arts: rhetorics of argument, formal and informal languages, mathematical calculi, “spiritual exercises,” pedagogical practices. As a result, even a mode of reflection that claims to apprehend its objects at their point of emergence from the “void” and the “unthought” will be described in terms of the contingent historical use of a particular array of such arts. These will be those arts through which a philosophical elite learns to fashion an illuminated self whom it imagines keeping watch at the threshold of the void for the emergence of things newly minted from nonbeing through their naming. It is the task of a certain kind of philosopher to fashion such a self. The task of the intellectual historian, however, is to describe the intellectual arts used in this “work of the self on the self,” and the historical circumstances and purposes governing their transmission and use. Continue reading …

This essay provides a historical redescription and reinterpretation of Alain Badiou’s major work, Being and Event. The work is approached historically, as a text that uses Heideggerian metaphysics to perform an allegorical exegesis of mathematical set theory and does so as a means of fashioning a supremacist spiritual pedagogy for a philosophical elite in the context of a national intellectual subculture.

IAN HUNTER is an emeritus professor in the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, University of Queensland, Australia. He has published a number of studies on early modern philosophical, political, and juridical thought, most notably Rival Enlightenments: Civil and Metaphysical Philosophy in Early Modern Germany (Cambridge, 2001). Professor Hunter has also published a series of papers on the history of “theory” in the humanities academy, including “The History of Theory,” Critical Inquiry 33 (2006), and, most recently, “Hayden White’s Philosophical History,” New Literary History 45 (2014).

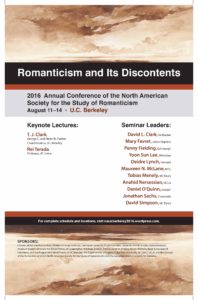

On Friday, August 12,

On Friday, August 12,