“As Often as His Heart Beat, the Name Moved”: Devotion and the “As if” in The Life of the Servant

by Rachel Smith

This essay considers an instance of medieval fictionality through the devotional text The Life of the Servant by the Dominican Henry Suso, specifically, through an examination of the “Servant’s” attempt to identify with Christ. Two forms of doubleness issue from this attempt, namely, the human servant seeking to embody the divine without remainder and his figuration as sinner and savior. Insofar as the text allows for a play between these polarities, the servant’s devotional practice can be understood as inhabiting the “as if,” or a kind of fictionality. The temptations of a devotional literalism—fiction striving to overcome its fictionality—is portrayed in the Life alongside a vision of devotion that retains the suspensions and play of the fictional.

This essay considers an instance of medieval fictionality through the devotional text The Life of the Servant by the Dominican Henry Suso, specifically, through an examination of the “Servant’s” attempt to identify with Christ. Two forms of doubleness issue from this attempt, namely, the human servant seeking to embody the divine without remainder and his figuration as sinner and savior. Insofar as the text allows for a play between these polarities, the servant’s devotional practice can be understood as inhabiting the “as if,” or a kind of fictionality. The temptations of a devotional literalism—fiction striving to overcome its fictionality—is portrayed in the Life alongside a vision of devotion that retains the suspensions and play of the fictional.

The essay begins:

In the early period of his devoted apprenticeship to “eternal wisdom” while he was yet a beginner, the fourteenth-century Dominican Henry Suso (c. 1295–1366) writes in The Life of the Servant of how “the servant” inscribed the name of the beloved on his chest as “a sign of love that would give testimony as an eternal symbol of the love between you and me, one that no forgetting could ever erase.” As courtly lovers write the name of their beloved on their clothes, so he

threw aside his scapular, bared his breast, and took a stylus in hand. Looking at his heart, he said, “God of power . . . today you shall be engraved in the ground of my heart.” And he began to jab into the flesh above the heart with the stylus in a straight line. He jabbed back and forth, up and down, until he had drawn the name IHS right over his heart. . . . Kneeling down he said, “My Lord and only Love of my heart, look at the intense desire of my heart. My Lord, I do not know how to press you into me further, nor can I. Alas, Lord, I beg you to finish this by pressing yourself further into the ground of my heart and so draw your holy name onto me that you never again leave my heart.”

. . . The letters were about as thick as a flattened-out blade of grass and as long as a section of the little finger. He carried this name over his heart until his death. And as often as his heart beat, the name moved. (chap. 4)

The servant seeks here to become one with the prayer composed of the name of Jesus, to permanently wear the name of the beloved to whom he is devoted. It is an embodied strategy to solve the problem raised by the injunction in 1 Thessalonians 5:16 to “pray without ceasing.” This inscription promises to overcome the predations of time, to deal with the anxiety of forgetting that “erases” the memory of the love between the soul and God, and with it, belief. It occurs following the first intense blush of love in which the servant enjoys two encounters with God and confidently declares to Wisdom, “Joy of my heart, this hour can never be lost to my heart” (chap. 2). However, despite the fullness of divine revelation in raptures that transcend time, the servant inevitably returns to the weight of the body and wonders what trace of these meetings with the beloved remained, how to realize such divine excess in a human life. By carrying the sign of this love in the flesh, the servant hoped he could not lose the beloved even while inhabiting the body. The scar was a permanent mark resting on top of the heart beating—keeping—time.

Inscribing and being inscribed by the name turned the servant into a book, his skin, parchment marked by letters from a stylus, available in turn for readers of the Life as a model for the spiritual path. This “certain Swabian friar” become the bearer of another name is fabricated as a living prayer and made available as an image of divine discipleship to those who encounter the text. The Life offers here another iteration in a chain of exemplarity textually transmitted, giving the servant’s life and body for the regard, consumption, and imitation of readers. The servant’s scarification echoes stories of figures as important as Ignatius of Antioch, whose martyrdom was included in the widely circulating thirteenth-century compilation The Golden Legend, where it says that the name of Christ was found not on but in the martyr’s heart, proving the efficacy of his “unceasing repetition” of Jesus’s name on the way to his execution. His heart and bones were said to be the only things untouched by the lions, and when his heart was cut open, the pagans saw the inscription “Jesus Christ” in gold letters.

This scene introduces a section of The Life of the Servant that lasts for a lengthy nineteen chapters, in which the servant details the bodily and imaginative practices undertaken by him in order to compassionately identify with the sufferings of Christ and his mother. These practices include penitential offerings for the servant’s sins and his imitation of divine suffering. It is on these chapters that this essay will focus. Devotion, for the servant, is not the adoration of the beloved from a distance but rather seeks to unite with Christ such that the servant becomes him. Devotional identification here entails the inscription of the beloved on the body, whether through stylus, ritualized bodily practice assiduously repeated, or works of imagination. The essay will consider the structural features of the servant’s striving to identify with Christ. It will show that two forms of doubleness issue from this attempt to become the beloved. The first is the tension between the human servant—finite flesh—seeking to embody the infinite divinity without remainder. The second is the figuration of the servant as simultaneously a sinner and Christ the savior. The fascination of the text in large part arises from the ways in which it wrestles with these performative contradictions.

Insofar as the text allows for a play between finite and infinite, sinner and savior, I will argue that the servant’s ascetic practice can be understood as one of inhabiting the “as if.” In other words, as a kind of fictionality. This is not the fictionality of the modern English novel but rather a historically specific account of the fabrication (fictio) of the self through ritual practice that renders the subject both oneself and another. Suso’s portrayal of the devotional “as if” offers a vision for a practice and a theology of exemplarity that does not operate according to an allegorical structure, which would entail the imposition of a form upon a content in which the aim is the latter’s defeat; it does not model the dream of the transmutation of letter into spirit. A vision of the play possible within devotional identification is represented by means of portraying the possibility of such play in ascetic practice, yet also through the ultimate failure and renunciation of the asceticism of the first part of the Life. Chapters 4 through 19, I will argue, work out the futility of an allegorical logic through a dramatization of its temptations—the temptation of a fiction attempting to overcome its fictionality—culminating in its defeat in chapter 18, in which the servant hears a divine voice tell him to desist from his bodily mortification. The ground of such temptation is already apparent in the scene of bodily writing that opens chapters 4 through 19. The servant, seeking a union with the beloved that transcends time, carves the name of Christ on his body, thereby seemingly overcoming the distance between himself and Jesus through the permanence of a scar; the body is forever marked, the name never lost. The servant, it seems, attains perfect success in the quest for union at the outset of his journey. Such embodied literalism is, however, represented as increasingly dangerous—courting death—as the text portrays the servant engaged in the acts of violent ritual repetition required to overcome the fear of a loss of memory and presence that insistently asserts itself, despite the initial inscription that promised to transcend time. Literalism—the notion that to say “I am Christ” is a truth that can be wrought in the flesh—is shown to be an attempt to overcome the peculiar suspensions, play, and doubleness of the devotional “as if.”

In order to unpack the notion of the “as if” that I see as operative in the Life, I will turn first to a very different medieval figure, the twelfth-century Cistercian Bernard of Clairvaux. The author of eighty-six sermons on the Song of Songs, in which he develops the allegory of the monastic soul as the bride of Christ, is not remembered for his life of self-denial. Bernardine views on asceticism were passed on to later medieval readers under the dominant note, Simone Roisin argues, of “moderation,” despite the fact that such a portrayal was not entirely consistent with his representation in sources like The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux, traditionally known as the vita prima. In bringing together Suso and Bernard, I hope to show that, although there are crucial and telling differences between the thought and forms of life of the two men, there are also important continuities between them. A decidedly unbloody Bernard might help us understand the representation of the servant’s asceticism, and not only by way of contrast. In order to do this, I will look to Burcht Pranger’s study of what he terms Bernard’s poetics of artificiality. I will then turn back to The Life of the Servant and its portrayal of the servant’s self-mortification. At the end of the essay, I will briefly compare this medieval example with some modern notions of the fictional. I will argue that there is a contrast between the novelization of imagination and the explicit artificiality of this instance of the literature of exemplarity. The hyperrealism of Suso’s fictional practice, although it is a making that makes real what is formed through the work of ritual repetition, is not an expression of credulity; he works against credulity. The point of his ascetic practice is to meet Christ through artifice, the artifice of ascetic imitation rendered explicit in order to become a manual for others to follow. Continue reading free of charge for a limited time …

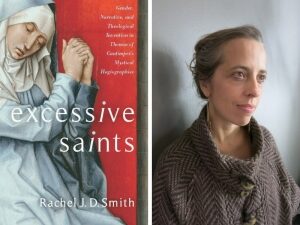

RACHEL SMITH is Associate Professor of Theology and Religious Studies at Villanova University. Her first book is Excessive Saints: Gender, Narrative, and Theological Invention in Thomas of Cantimpré’s Mystical Hagiography (Columbia University Press, 2018). She is currently writing a book on mystical theology for Brill Publishers.

RACHEL SMITH is Associate Professor of Theology and Religious Studies at Villanova University. Her first book is Excessive Saints: Gender, Narrative, and Theological Invention in Thomas of Cantimpré’s Mystical Hagiography (Columbia University Press, 2018). She is currently writing a book on mystical theology for Brill Publishers.